Los Angeles City Council Violates California Brown Act and First Amendment Using a Digital Speaker Registration System

Nighttime photo of Los Angeles City Hall.

I. ORIGINS AND PURPOSE OF THE BROWN ACT

The California Brown Act was enacted in 1953 following a series of local-government scandals that revealed city councils and local boards were routinely meeting and making decisions behind closed doors. The legislation was sponsored by Ralph Brown, a California Assembly member who became aware of these abuses through press investigations and constituent complaints.

At its core, the Brown Act is straightforward and commonsense. It requires that all local legislative bodies—at the city and county level, including state-created bodies such as the California State Bar—conduct their decision-making meetings openly and in public. These meetings must allow public attendance, provide opportunities for public comment, and be properly noticed. The meetings are recorded, and public comments become part of the official public record.

The Act does more than set procedural expectations. It imposes criminal liability on government officials who knowingly violate its requirements, including violations of the public’s right to comment. Each violation may be charged as a misdemeanor, punishable by a fine of up to $2,000 and up to one year in jail, with each violation treated as a separate offense.

II. EXPANDED PROTECTIONS WITH SENATE BILL 707

Over time, California legislators have expanded the Brown Act’s protections to address modern realities. Most recently, the Legislature enacted Senate Bill 707, which mandates that public bodies allow virtual attendance and accept public comment remotely.

All California government agencies are required to comply with these new mandates by early July 2026.

With these additions, California now has the strongest statutory protections in the nation for public participation in government meetings. In contrast, most other states’ open-meetings laws merely require that meetings be open to observation and that records be kept. They generally do not codify a statewide right to public comment at every meeting, nor do they impose meaningful penalties when officials suppress speech.

Some municipalities in other states have adopted local policies permitting public comment, but these policies typically lack enforcement mechanisms or penalties. As a result, in much of the United States, the public’s legal right is limited to watching government proceedings—nothing more.

Even New York City, one of the largest and most influential cities in the world, lacks a comprehensive legal framework guaranteeing public comment at every public meeting. In practice, this silences millions of voices. A system that allows the public only to observe, but not speak, is passive and fundamentally inconsistent with the democratic free-speech principles on which the United States was founded.

III. VIRTUAL PUBLIC COMMENT

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the City of Los Angeles had no difficulty accepting virtual public comment across its public meetings. Using existing teleconferencing infrastructure, the city successfully allowed members of the public to participate remotely for years. That infrastructure still exists today.

Through public records requests, it has been confirmed that the City of Los Angeles continues to retain all necessary electronic hardware and software from that period, including microphones, speakers, cameras, and active software licenses. No additional equipment, configuration, or expenditure is required for the city to resume virtual public comment immediately—well in advance of the Senate Bill 707 compliance deadline of July 2026. Despite this, the city has chosen to delay reinstating virtual public participation.

Further public records obtained from the Los Angeles Information Technology Agency (ITA) reveal an even more striking fact: the city’s teleconferencing platform—Zoom—is provided at no cost to all city agencies. This includes full access to features such as recording, virtual public comment, webinars, chat logs, automatic closed captioning, and related functionality.

This type of arrangement is common in government. Software companies frequently provide heavily discounted or free licensing to public agencies, similar to nonprofit pricing models, in exchange for long-term institutional adoption and future integration opportunities. In this case, the entire Zoom platform is free to the city.

However, public records show that despite this citywide free licensing, Los Angeles has required one specific category of city entities to pay for Zoom licenses out of their own budgets: the neighborhood councils.

Los Angeles is unusual in that its neighborhood council system is formally established in the City Charter. There are 99 neighborhood councils, each composed of volunteer board members who live and work in the communities they represent. These councils serve as a direct and accessible conduit between residents and city government, particularly in a city as geographically sprawling and decentralized as Los Angeles. Each neighborhood council receives a modest annual budget—approximately $30,000—to support local initiatives and community needs.

Despite being an official city government agency, neighborhood councils have always been forced to pay for teleconferencing access themselves, even though Zoom was already licensed and available at no cost to all city agencies. This effectively forced neighborhood councils to divert scarce public funds to pay for software that the city already had.

The implications are significant. Neighborhood councils are often far more accessible to residents than City Hall itself. They meet locally, are staffed by volunteers from the community, and provide a public forum where constituents can realistically participate—especially for residents whereby traveling downtown is impractical due to distance, cost, work schedules, or mobility limitations. By imposing unnecessary costs on neighborhood councils and delaying the restoration of virtual public comment citywide, Los Angeles has further limited meaningful public participation.

Taken together, these facts undermine any claim that logistical, technical, or financial barriers prevent the city from restoring virtual public comment. The capacity exists. The infrastructure exists. The cost is zero. The delay is a choice.

Screenshot of public records request submitted to the Los Angeles Information Technology Agency (ITA) back during September 24, 2025. The document shows that the Zoom platform is free for the City of Los Angeles to use. The full public records reply of the Information Technology Agency in PDF format can be found by clicking here.

Screenshot of a list of electronic hardware used in every public meeting room at the Los Angeles City Hall. This screenshot only shows a portion of the complete inventory. The inventory shows the quantity, make, and model of every microphone, sound system, and video camera system used by the Los Angeles city government. This document comes from a public records request submitted to the Los Angeles Information Technology Agency (ITA) on September 24, 2025. The complete inventory released from this public records request can be found in PDF format by clicking here.

IV. REMEDIES FOR BROWN ACT VIOLATIONS

The Brown Act also provides a built-in mechanism to remedy violations when public speech is chilled. This takes the form of a “Demand for Cure and Correct,” an administrative complaint submitted to the public body involved and typically to the city clerk. The demand requires only that the complainant identify:

The government body

The meeting date

The specific violation

A request for corrective action

The remedy itself is straightforward. The public body is required to halt proceedings and reset the public comment period to allow affected speakers to provide their full remarks. This remedy may be requested verbally during the meeting or formally in writing. If the body fails to cure the violation, any actions taken during that meeting are rendered void. The body must reconvene—no later than its next regular meeting—after providing proper public notice and must address and correct the violation, including restoring the affected speaker’s opportunity to comment. Failure to do so exposes officials to both civil and criminal liability for acting in concert to violate the law. The City Attorney’s Office is obligated to accept these complaints, including on-site during meetings, and to advise officials of violations and recommend cessation of proceedings when necessary.

V. LOS ANGELES CONTINUES REPEATEDLY VIOLATING BROWN ACT

Los Angeles is widely regarded as a center of activism and government reform. Many landmark laws and high-profile lawsuits originate there, and its status as the entertainment capital of the world ensures global attention. This visibility creates strong incentives for city officials to suppress dissenting and critical voices during public meetings.

Public comment in Los Angeles requires speakers to register in advance by entering a name into the speaker queue. Speakers are not required to use their legal names; fictitious names are permitted so long as the speaker responds when called.

There are two distinct public comment periods:

Agenda Item Comment - pertains to items listed on the agenda

General Public Comment - anything not on the agenda

Each category provides a defined amount of speaking time. These sections being distinct is moreso symbolic and to help the clerk organize comments and register whether speakers are for or against a particular item, NOT as a bar to limit what you can say during a particular segment.

One of the most common tactics used to cut speakers off is the arbitrary and unlawful assertion that a speaker is “off topic.” This tactic is disproportionately used against speakers who are sharply critical of city officials. The purpose is not enforcement of decorum, but disruption—throwing speakers off their train of thought, provoking emotional reactions, and reframing the speaker as the aggressor rather than the victim. This tactic was directly addressed in federal court when David “Zuma Dogg” Saltsburg and Matthew Dowd, along with multiple co-plaintiffs, sued the City of Los Angeles for violating their First Amendment rights.

The lawsuit was filed on September 16, 2009, and culminated in an eight-day jury trial beginning in late January 2014 and concluding around February 10, 2014. The case spanned several years due to amended complaints, changes in representation, and the fact that some plaintiffs passed away or withdrew.

Initially self-represented, the plaintiffs were later represented by the Los Angeles chapter of the nonprofit known as Public Counsel. The jury found that the City of Los Angeles had violated the plaintiffs’ First Amendment rights during public meetings. The court held that the public comment period belongs to the speaker for the full duration of their allotted time and that chilling speech during that period constitutes a violation of core First Amendment protections.

The court made clear that, absent criminal threats or unlawful conduct, speakers may criticize the government on any topic during their allotted time. Although the plaintiffs were awarded only nominal damages of one dollar, the case established a clear public record of unconstitutional conduct and created binding precedent for future claims.

Documents from David Saltsburg lawsuit

VI. MODERN DAY BROWN ACT VIOLATIONS USING SOFTWARE

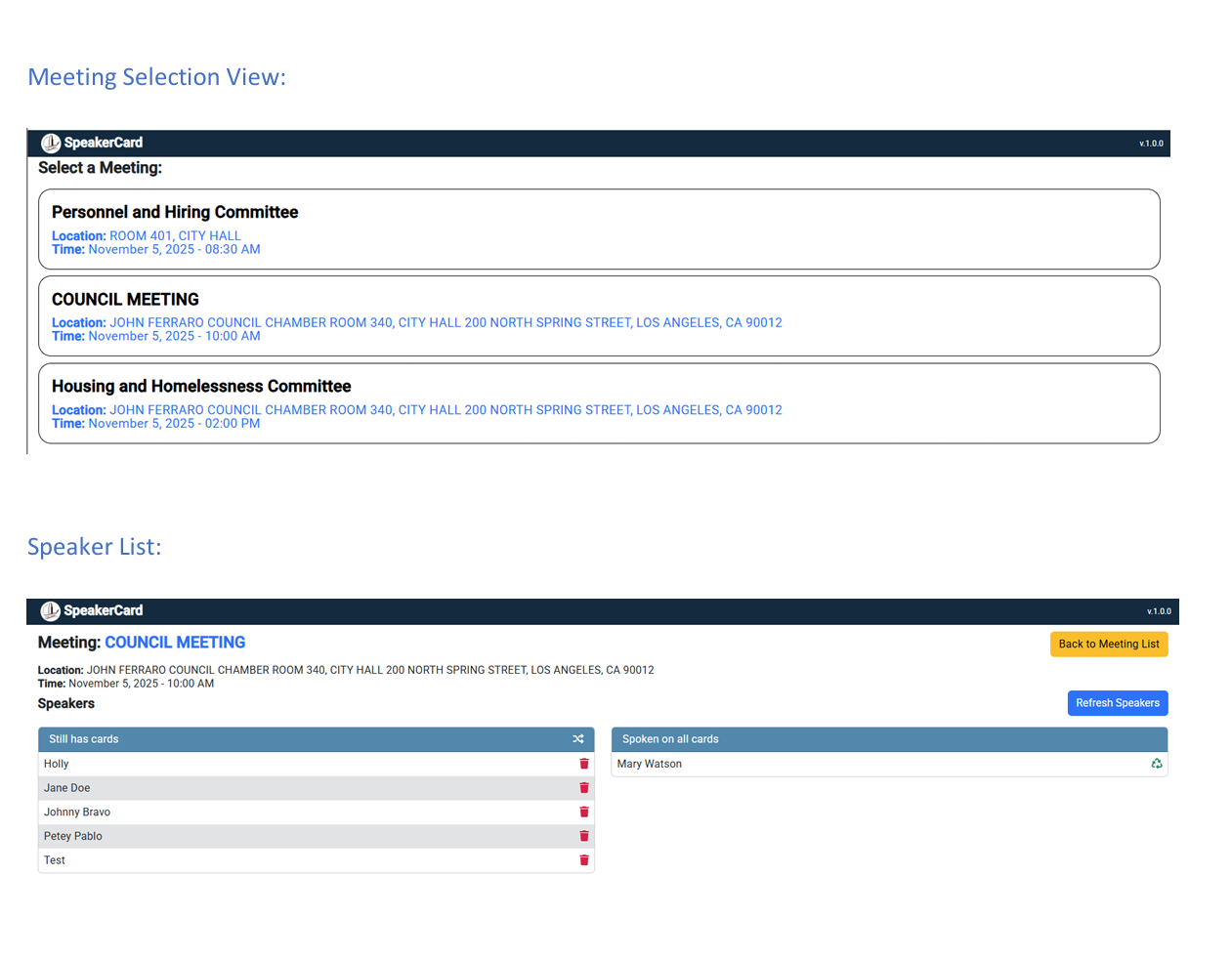

Despite this ruling, Los Angeles continues to suppress public comment—now through digital means. The city replaced its paper-based speaker sign-in process with a computer kiosk system requiring speakers to register electronically. The system collects a name and the agenda items the speaker wishes to address. City council members, the city clerk, and the council president have direct control over this system. Its features include the ability to:

Delete registered speakers

Reorder the queue

Mark speakers as having already spoken

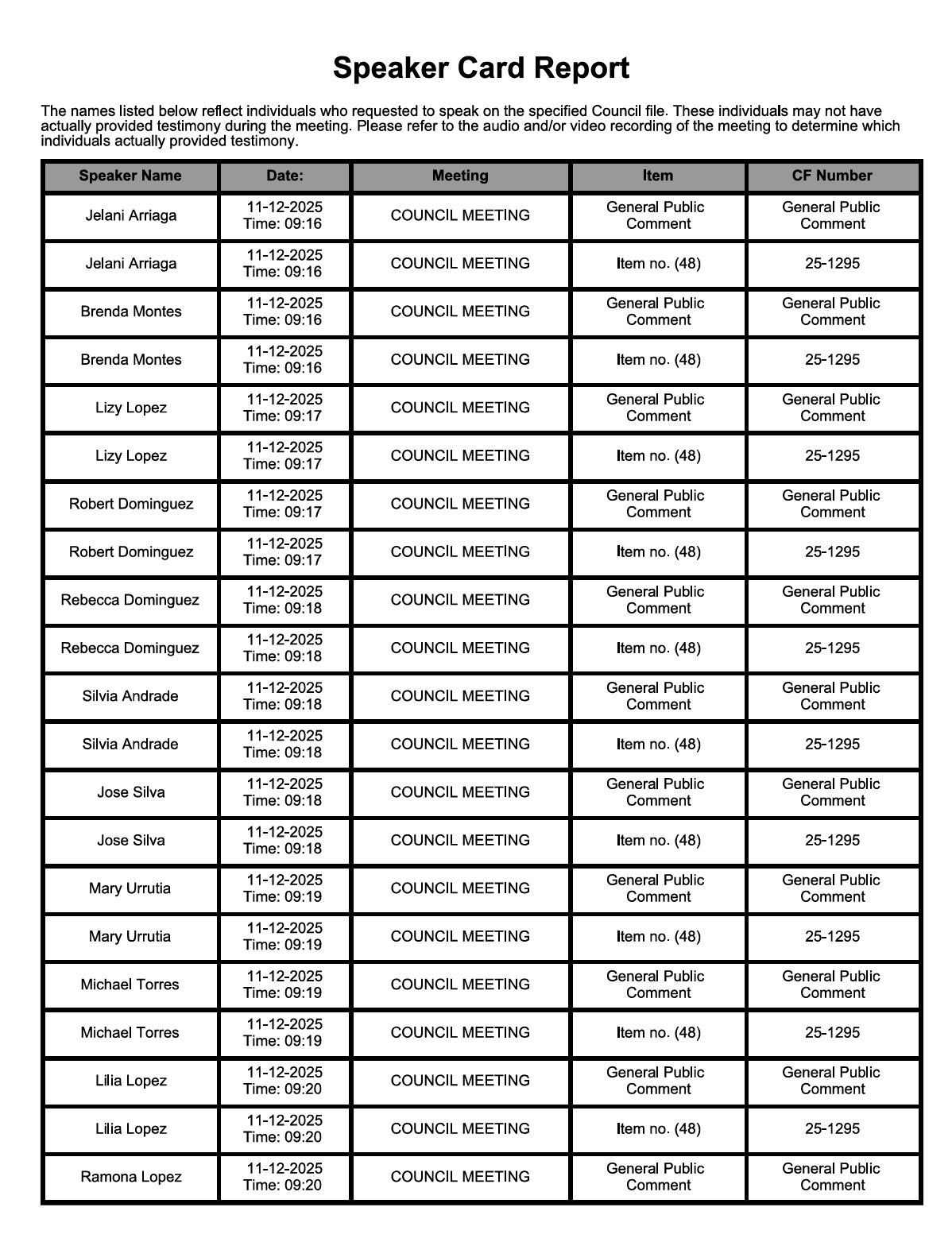

Council members access the system through single sign-on credentials tied to their official city accounts, meaning all actions are logged, time-stamped, and attributable to specific officials. The data is stored electronically and is auditable.

Although public records do not identify the platform, the system’s appearance suggests it is either custom-built or implemented through Microsoft’s Power Platform.

The city has leveraged this technology to introduce plausible deniability when speakers’ names are skipped, deleted, or ignored. Compounding the issue, the system provides no receipt or confirmation record to speakers after registration, nor does it display a public roster of registered speakers.

By contrast, the former paper-based system allowed speakers to visually confirm their place in line and retain proof of submission.

No public training is provided on how to use the kiosks, even though records show city officials receive formal training. The kiosks themselves are poorly labeled and difficult to locate.

This has produced a new “cat-and-mouse” dynamic in which speakers feel compelled to submit multiple entries to ensure they are called. Public records confirm the system is configured on a first-in, first-out basis, yet officials routinely claim names do not exist, have already spoken, or were “too far down the list.”

Ironically, all such manipulations are digitally recorded.

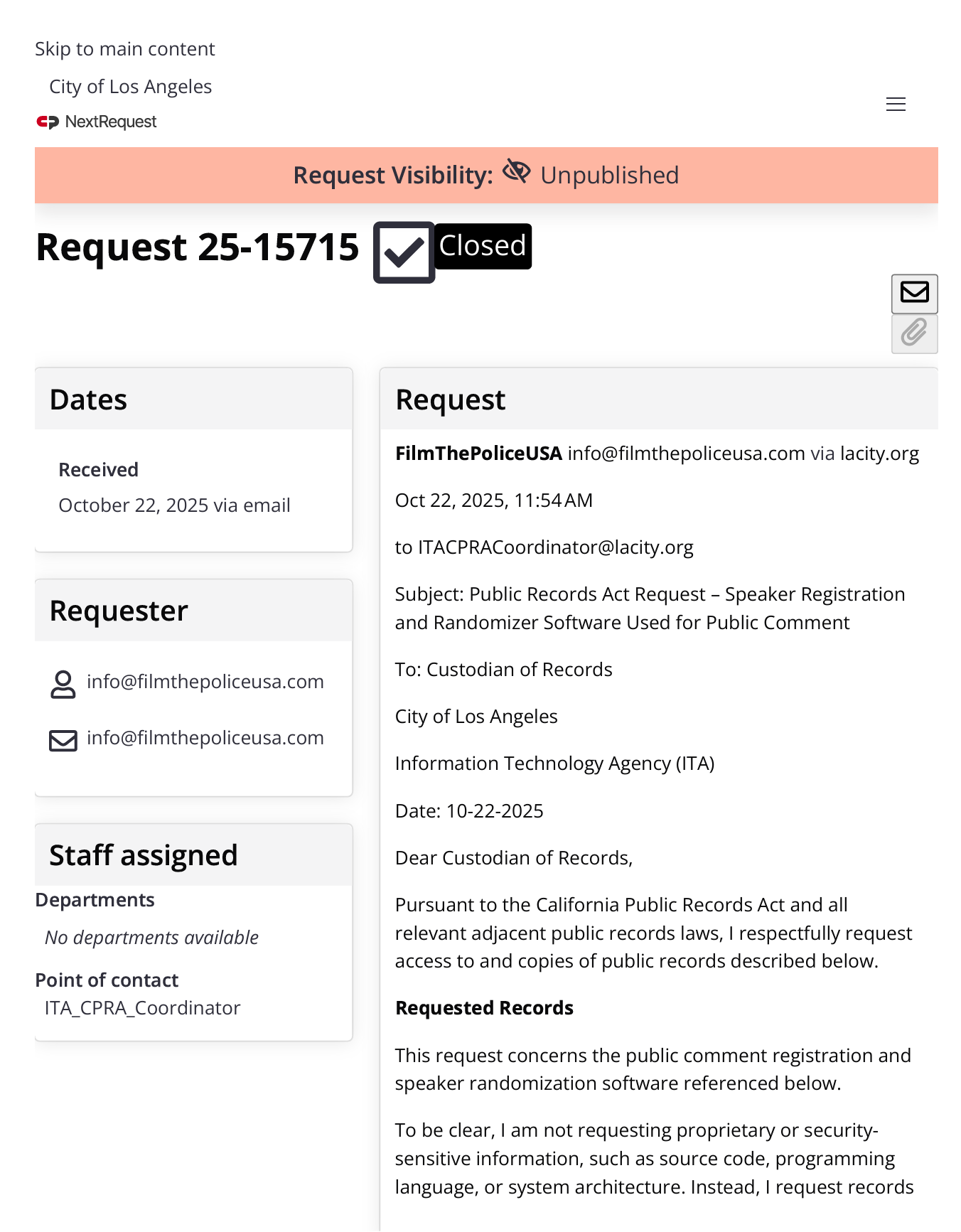

Most troubling, the City of Los Angeles has denied—through official public records responses—that this system exists at all, despite city council livestream footage clearly showing the software in use on officials’ computer screens. City officials have even taken to giving members of the audience and other council members instructions to not listen to certain comments given by members of the public before the public comment period begins. They do this by having the presiding Deputy City Attorney issue this warning. This is a classic example of prior restraint, a tactic intended to chill protected free speech.

Screenshot of the Los Angeles City Council speaker queue software system seen from the perspective of an account logged in as a City Councilmember. The screenshot shows the name of the meeting, a list of all registered speakers, and buttons to delete a speaker, shuffle the order of speakers, and mark a speaker as having spoken. This image comes from a public records request submitted to the Los Angeles City Clerk on November 7, 2025. This document is available in PDF format by clicking here.

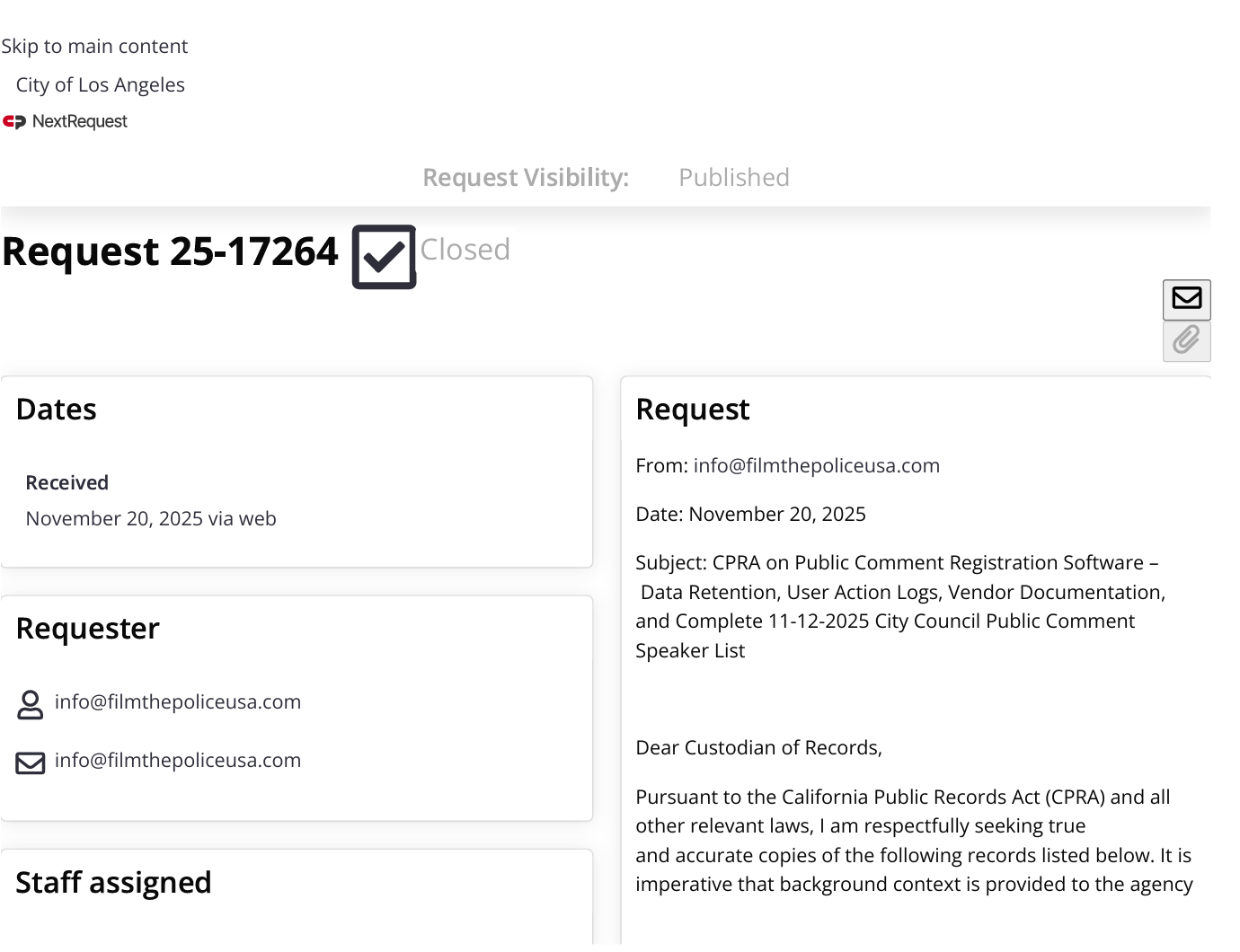

Screenshot of public records request submitted on October 22, 2025 to the Los Angeles Information Technology Agency (ITA) asking for proof of the public comment registration software. The ITA denied the existence of the software system but then simultaneously directs the requester to file the request with the Los Angeles City Clerk. This full document is available in PDF format by clicking here.

Screenshot of the public records request submitted to the Los Angeles City Clerk on November 1, 2025 asking for proof of the existence of the public comment software system. This request was submitted after the Information Technology Agency denied the system’s existence on October 22, 2025. This document is available for download in full in PDF format by clicking here.

Screenshot of training instructions given to Los Angeles city council members on how to use the public comment software system. This record proves that the City of Los Angeles proactively teaches City officials how to use the public comment registration software system, namely council members and the City Clerks, with training coming directly from the City Clerk’s office. This image comes from a public records request submitted to the Los Angeles City Clerk on November 18, 2025. This document is available in full to download in PDF format by clicking here.

Screenshot of a list of names registered to speak during public comment at a routine public hearing of the Los Angeles City Council on November 12, 2025. The completed document shows the actions taken by each council member to each registered name and the timestamp for when they took said action. This proves that the software system saves all names and actions within the system for each and every meeting. This document was obtained by submitting a public records request to the Los Angeles City Clerk. This document is available in full to download in PDF format by clicking here.

Screenshot of public records request to Los Angeles City Clerk submitted on November 20, 2025 seeking the records for the data retention policies of the public comment software system. The Los Angeles City Clerk did not fulfill the policy portion of the request but provided other records pertaining to metadata of the software system, indicating that the clerk’s office does indeed store these records. Since the files are all electronic, it is highly likely they store these files permanently in electronic format. This document is available in full to download in PDF format by clicking here.

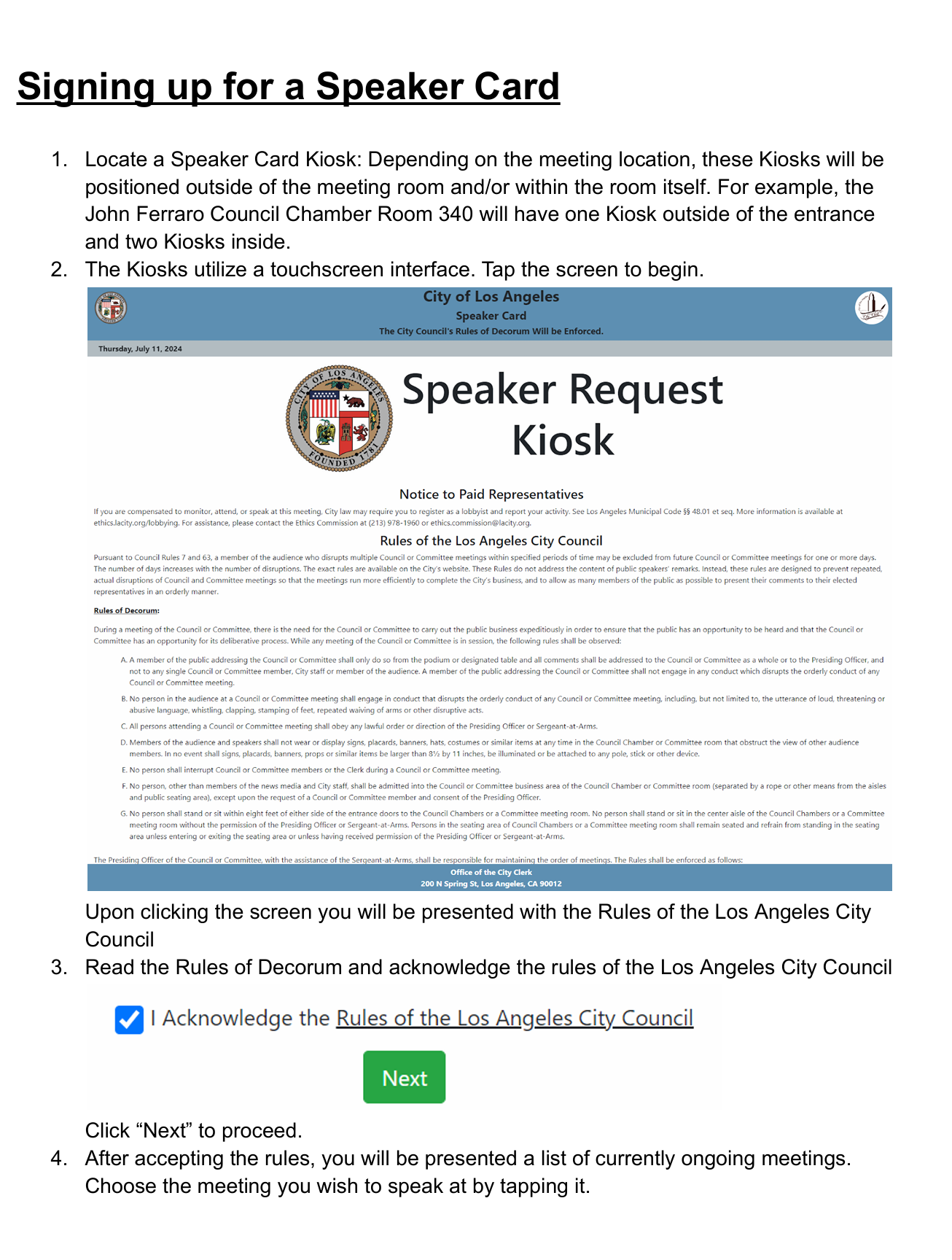

Screenshot of an educational pamphlet now being provided in paper form at speaker kiosks to teach members of the public how to use the speaking queue software system. This pamphlet is new and never been done before by the city, a result of the pressure applied during this investigation. The computer kiosks still remain indescribable and without any signage labeling them for their intended purpose, but these pamphlets have been observed to be available at some kiosks at City Hall. This document came from a public records request to the Los Angeles City Clerk on November 26, 2025. This document is available in full to download in PDF format by clicking here.

VII. ENFORCEMENT FAILURES AND PUBLIC CORRUPTION

Although there have been no recent prosecutions for Brown Act violations despite extensive documentation, the absence of charges does not mean the harm is theoretical. The purpose of these violations is deterrence—using fear and frustration to discourage public participation. Under the City Charter and formal agreements, the City Attorney is responsible for prosecuting Brown Act violations. However, when violations rise to the level of public corruption or civil rights abuses, the Los Angeles County District Attorney has authority to prosecute through its Public Integrity Division.

This is particularly significant given that violent crime in Los Angeles continues to decline, while public corruption—especially collusion involving land use, water rights, capital infrastructure projects, and homelessness programs—remains pervasive. By the city’s own reports and public testimony from residents, these forms of corruption constitute a substantial share of systemic harm in Los Angeles.

CONCLUSION

The California Brown Act was designed to ensure government accountability through transparency and public participation. In Los Angeles, however, a documented pattern of suppression—now amplified by digital tools—continues to undermine those guarantees. The law is clear, the remedies exist, and the violations are recorded. What remains absent is meaningful enforcement. Thanks for tuning in. Please be sure to subscribe to our newsletter and support our work via the links below.

If any of the above links containing the documents do not work for some reason, you can access all of the documents via the DocumentCloud links below for free: